Forever Alive, Forever Forward

From the June issue of Outside magazine

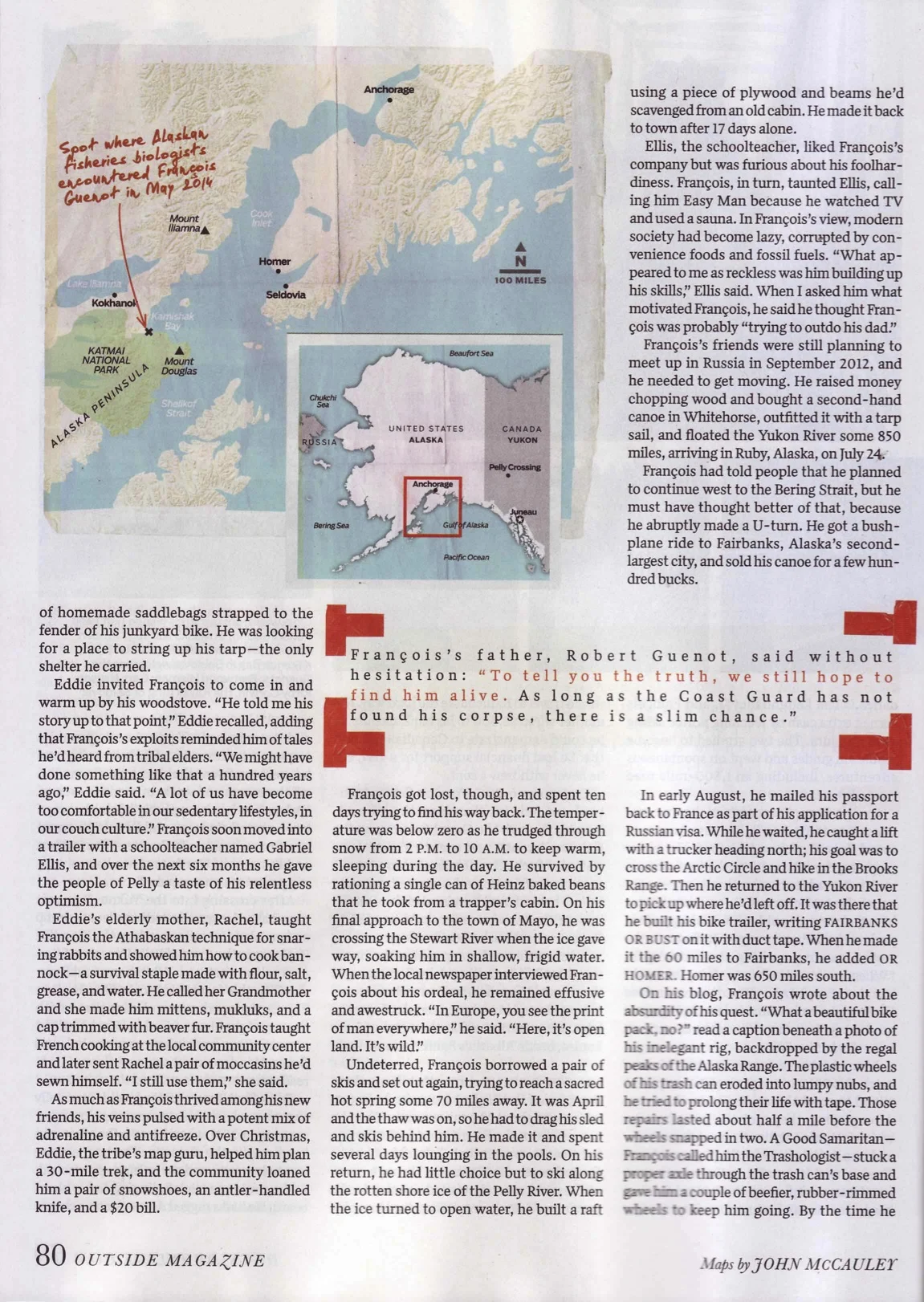

On the morning of May 26, 2014, two Alaskan state biologists were in a Cessna floatplane, counting fish from the window as a pilot took them down the Alaska Peninsula, a huge, curved harpoon of land that juts toward Russia from the southeast. Just then they were in an area fronting Kamishak Bay, on the coast north of Katmai National Park.

Seen from above, the peninsula’s landscape looks like a runny soufflé, a cracked and wrinkled pillow of mossy tundra perforated with hundreds of inkblot lakes. In the distance, the biologists could see glaciers twisting off the flanks of Mount Douglas, the 7,021-foot volcano that stands sentry over one of Alaska’s diciest water passages: the maritime pinball machine known as the Shelikof Strait. No roads lead in or out of where they were, and reaching the nearest village requires several days of bushwhacking through grizzly-infested alder thickets.

Suddenly, one of the men spotted the white cork floats of a fishing net. “Whoa! That’s a gill net,” Glenn Hollowell shouted to his partner, Ted Otis, over the hum of the propeller. The net was stretched across the mouth of Amakdedori Creek, blocking it entirely. They stared in disbelief at such a blatant violation of fisheries regulations, in a place where a major sockeye salmon run was only two weeks away. The sea was remarkably calm, and their pilot offered to land the plane on its pontoons.

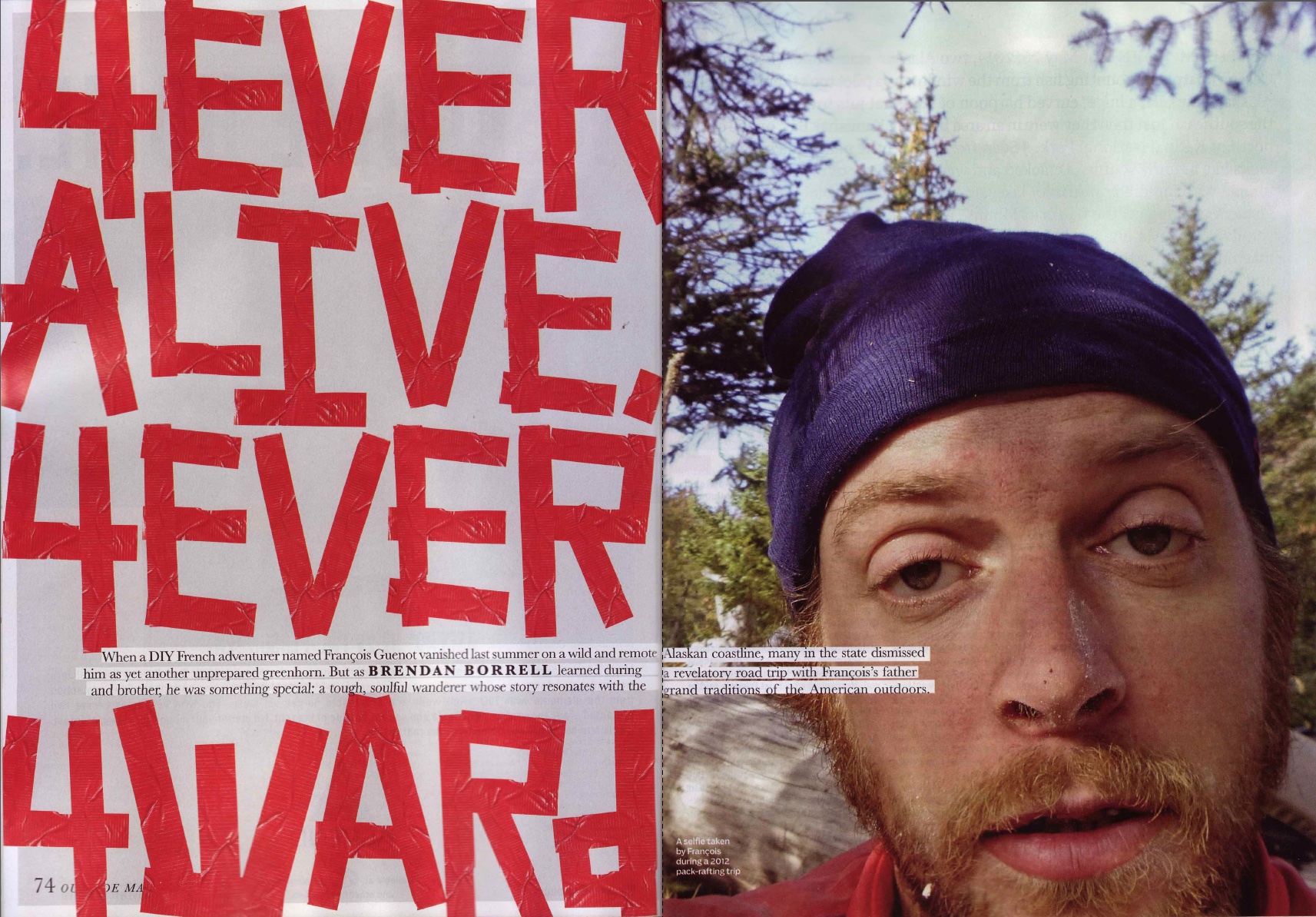

When the biologists hopped out onto the beach, they were greeted by a man with a disarming smile and a thick French accent. “I am François!” he said, holding out his hand. François was a spare, muscular guy in his mid-thirties with a sunburned nose, a scraggly beard, and a bandana wrapped around his mostly bald head. His clothes were unwashed and tattered, and he reeked of wood smoke and body odor. He looked like a feral orphan, a postpubescent Little Prince who’d spent too many years stranded in the Sahara.

Read the rest here